“There were never two more competitive sides when we played each other over a period of four or five years” – Jack Charlton on Leeds-Chelsea games.

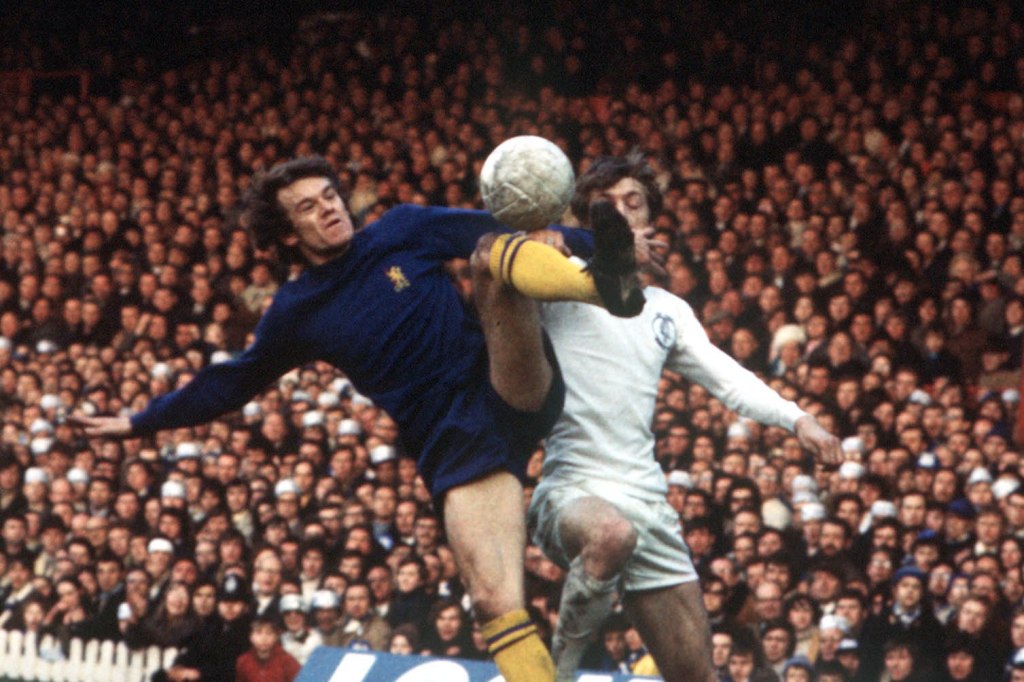

Chelsea v Leeds United is one of English football’s most notorious and storied rivalries. Forged in the crucible of the 1960s, when the ball was as hard as stone, the allowance of one substitute was a revolution (the game’s gone!), the pitches were quagmires, fighting was as common on the pitch as off it, and the rumours of corrupt officials were rife.

Stereotypes permeated clubs coverage and reputations. Leeds were the northerners, hard men who took no prisoners. Don Revie’s lads, traditional, straight, settled at home, who played bingo with the boss over pints of bitter.

Chelsea’s team were southerners, frequenting London’s West End, at a time when the 60s was in full-swing. Likely lads, better dressed, who gave as good as they got. Chelsea were everything the north hated, and Leeds were everything the south despised.

“We hated them and they hated us” Chelsea’s Ian Hutchinson said of the teams.

The rivalry is born

The flames roared and ebbed over the years, but the match that sparked the rivalry was a Tuesday night, late April, 1963. Both teams in Division 2 – now called the Championship – both heading for promotion. Revie’s revolution at Leeds had begun, but a compact schedule proved too much for his young side. As the country thawed from the big freeze, a rivalry sparked into life. Leeds needed a win, the 2-2 draw kept the Whites in Division 2. Chelsea were promoted. Evenly matched, similar styles, a divisional rival, the seeds were planted. And when Leeds were promoted as Champions the following season, the rivalry would resume in earnest.

In the decade that followed the two teams would meet in pivotal games. Each meeting new enmities between players would form, revenge would be taken for previous infringements. The flames of injustice burned. Jack Charlton kept a little black book of players who had wronged him or the club. He would never forget a thing or suffer an injustice without arranging a reprisal. Chelsea and Leeds had famous reputations, notoriously aggressive. Neither would back down. And each new clash escalated the burgeoning hatred between the sides.

When Chelsea dumped Leeds out of the FA Cup in 1966, with a large hand from the referee who disallowed two perfectly good goals. The injustice propelled them to a 7-0 victory – the widest margin recorded – when they next played at Elland Road.

The rivalry went on like this – both sides hacking chunks out of each other – Jack Charlton scribbling away. The furious battles became box office and peaked with the 6th most-watched broadcast in UK television history – the 1970 FA Cup Final.

The 1970 FA Cup Final – The rivalry goes global

The first match held at Wembley was as even as they come. Held on a pitch that was at least 50% sand – Leeds Terry Cooper would later quip that “you’d need hooves to play on that pitch”. Chelsea’s goalkeeper Peter Bonetti made save after save to deny the Whites, pipped to the Man of the Match by Eddie Gray. Leeds cleared the ball off their own goal line twice, and hit the woodwork three times at the other end. Extra time couldn’t separate the sides, and this was before the advent of penalties, and so, for the first time since 1912, the FA Cup Final went to a replay.

So on 29th April 1970, over 20 million people tuned in to what would become known as the most brutal game in English football history. Webb, Cook and Hausmann all snapped into Leeds players early – the ball an afterthought – Bremner snarling at the ref, the tone set. But it was Leeds who had the early chances and looked the better side for much of the two ties. “We must be the unluckiest team in the world” said Don Revie.

When Mick Jones thundered in a shot past a hobbling Peter Bonetti, it wasn’t undeserved. And though fiercely competed, it was not yet the brutal spectacle it would become. Though far more fouls were called against Chelsea, as Leeds had the better of possession and chances. Chelsea were constantly nibbling at Leeds, a tactic that would eventually tip them over the edge.

It was a little into the second half when tempers flared. First Cooper took studs to his thigh – ripping his shorts to bits which he presented to the referee, who waved away his appeals for a foul. Moments later Peter Osgood went through the back of Jack Charlton – who was not want to wait on the referee’s justice, he leapt up, spun around, and planted a knee straight into the Chelsea player.

With less than fifteen minutes left and the game being controlled by Leeds but with neither side able to create anything clear cut, the match turned on a chip to oncoming Osgood who’s bullet header equalised for Chelsea. It was ten minutes later that perhaps the most egregious incident occurred when Leeds captain Billy Bremner was kung-fu kicked in the back of the head in the penalty area. A challenge beyond belief then, it would be a red card and penalty several times over today.

Hugh McIlvanney later wrote that “at times it appeared that Mr Jennings would give a free kick only on production of a death certificate”.

If the Final had turned into a 15-round prize fight, it was Chelsea who dealt the knockout blow to break Leeds hearts. When the Blues lifted the UEFA Cup Winners Cup the following season it would prove the high water mark for Chelsea.

Leeds own high water mark came five years later in the Parc des Princes in Paris in exceptionally controversial circumstances. Denied two clear penalties, and a goal ruled out only after Bayern’s captain spoke to the referee, the unexplainable incompetence stank of conspiracy to the incensed Leeds crowd. To this day the Leeds fans sing “We are the Champions, The Champions of Europe” and Bayern Munich joined the list of Leeds most hated rivals.

Hooligans and the wilderness years

When the 70s turned to the 80s, Chelsea and Leeds fates were mirrored. Both clubs found themselves in the second division for spells. And while the country suffered politically and economically, fans found an outlet for their frustrations on the terraces. And while the clubs suffered financial problems off the field and relegation on it, both fan bases struggled with violence, hooliganism and racism.

With neither team looking particularly competitive on the pitch, the fan bases and associated firms became competitive off it. Fighting regularly broke out between fans in games during the 1980s, before, during, and after games. In one particularly explosive incident, as Chelsea won 5-0 to secure the 1984 Second Division title, Leeds fans responded to what they saw, by removing a pole from the nearby scaffolding and bashing Chelsea’s new scoreboard inoperable.

The narrative around football authorities, the police and government throughout the 1980s, was over how to address the growing violence in football was centred around punishing fans labelled as “hooligans” whether they were in the wrong or not. It was a line of thinking that, in part, led to the tragedy at Hillsborough. Chelsea and Leeds would play the week after the disaster, the minute’s silence held impeccably. Slowly the narrative began to change from demonising all football fans, to focusing on their safety.

The 1990s – The Battle of the Bridge

By the mid-90s the clubs were once again back in the big time. Leeds had won the title in 1992 – becoming the last true champions of English football – the last team to win what was then the First Division, and what would be known after as the Premier League. And by the 1996-97 season, Chelsea had a team that could compete again.

On 7th December 1997, Leeds enigmatic captain of Don Revie’s great Leeds team that had birthed the rivalry with Chelsea, died. In a small church in Old Edlington four days later, a collection of some of the most decorated and celebrated players of our great game gathered to pay their respects. Names familiar to historians of Leeds will recognise well – Giles, Hunter, Clarke, Gray and Lorimer. David Batty, playing for Newcastle at the time, paid tribute to his hero, and the manager who gave him his debut at his boyhood club.

Former Leeds captains bore a tribute: “To Leeds United’s greatest captain. It is an honour to follow in your footsteps.” And the death of the legend crossed footballing rivalries. The figure of Sir Alex Ferguson cut a lone and sombre shape in the Yorkshire village mourning the fellow Scotsman he had known “for a long time”. While among the crowd of fans, a Manchester United supporter stood next to a Leeds fan to pay their respects.

Alan Ball said of Bremner: “Having played against all of the world’s greatest players I knew that every time I came face to face with Billy it would be the toughest game of my life.” Bremner’s likeness is chiselled in stone, emblazoned on Elland Road’s East Stand, his words that have become a club motto: ‘Side before self, every time’. He was 55, and mourned today as keenly as ever.

Two days after the funeral Leeds travelled to Stamford Bridge – the venue that Bremner had made his Leeds debut 38 years earlier. The Leeds captain in 1997 was another fiery Scottish midfielder with red hair – David Hopkin. The Chelsea side that faced Leeds that day, featuring Zola, Flo, Wise, Duberry and Leboeuf, would go on to win the FA Cup that season for the first time since that famous 1970 Final. The minute’s silence for Bremner – held with grace from the London crowd – was the calm before the storm.

The referee’s whistle broke the silence, the crowd roared, and then the battle began. The two sides weren’t so much channelling Bremner as they were a whole era of football thought consigned to the past. Graham Poll though hadn’t got the memo.

Tempers were flying within minutes. Hasselbaink and Wallace went down under Chelsea attention, but Lucas Radebe’s enthusiastic tackle through the back of Gianfranco Zola, without consideration for the ball, set the tone. Though he denied doing so, it was clear that George Graham had sent this Leeds team out to hurt Chelsea. But Chelsea gave as good as they got.

The first half of that game was one few will forget and you have to think – looking back on this 60 year rivalry – the most tempestuous, if not the most brutal, ever played between the sides. By the end of the half, eight yellow cards had been handed out by Graham Poll, and Leeds had been reduced to 9 men by the referee.

“It was ludicrous because in many ways the referee was pretty lenient at times.. the tackles were just flying in. I don’t think you can argue at all about the sendings off” – Alan Hansen’s comments on Match of the Day were a fair reflection.

It was an odd but stupid first yellow for Gary Kelly, not retreating 10 yards from a corner, but, diving in like a man possessed at every opportunity meant he was bound to pick up another sooner rather than later. Another who saw red before he got a red was Alfie Haaland – yes the father of that famous Manchester City striker. Haaland was hacked at by Roberto Di Matteo, which Haaland hadn’t cared for. And after also not enjoying a little talk he had with him while Leeds had a throw-in, gave him a sharp kick. When Dennis Wise went in hard on Rod Wallace, after a Michael Duberry tackle that was full of vigor, Haaland – excited – smashed the ball out of Wise’s possession, and, deciding that wasn’t quite satisfying enough, gave him a good kicking after.

There were 21 fouls in the first 30 minutes and if the game were to be re-refereed today, there would be significantly more sendings off than just the two.

A now-disciplined (funny that) 9 men of Leeds shut out Chelsea for the entirety of the second half. Consigning the Londoners to long shots and besides a fine Nigel Martyn save and a couple of wayward headers, Leeds didn’t look particularly threatened. And the ‘Battle of the Bridge’ ended goalless.

The Modern Era

During the late 1970s and 1980s, both Chelsea and Leeds suffered relegation and went through financial troubles. This roughly equal status had kept the rivalry alive. But as Peter Risdale’s “dream” sent Leeds tumbling through the divisions and from one incompetent owner to another, Chelsea went the opposite path.

When Leeds were relegated in 2004, Chelsea had won 11 major honours in their history, and been English champions once. Leeds 9 major honours, and English champions three times. But when Roman Abramovich bought Chelsea and took Premier League investment to yet another level, he also filled up their trophy cabinet.

While Leeds were relegated to League One and losing to a postman from Histon, Chelsea won 21 major trophies, were English Champions 5 times and won 2 Champions Leagues. Next to that line of silverware Leeds biggest achievements were two promotions and beating Manchester United once in the FA Cup. Until Leeds United are restored to their former glory and can be competitive regularly near the top of the Premier League, this once great rivalry will continue to be one-sided. Leeds can point to their 3-0 win, perhaps the high-point of Jesse Marsch’s time at Leeds.

The brutality seen in previous incarnations of these battles will surely be consigned to the past. The game has moved on, and probably for the best. But the fans keep the flames burning. At almost every game you will hear Leeds fans singing of “shooting the Chelsea scum”. You will also hear Chelsea fans singing “we all hate Leeds”. With Leeds competent new owners and upward trajectory, and Chelsea seem to be stalling, we may see the latest chapter in this rivalry burst into life again. This new generation will have to write their own stories, and it might begin in the FA Cup, where so many of their most fierce battles have taken place.

Daniel Farke is a record breaker. He holds the highest win percentage of any manager in the club’s history, and recently broke a record for consecutive wins that hadn’t been broken since 1931. He can break one more record for Leeds United – beating Chelsea in a cup game.

Written by Adonis Storr @theadelites

SHOP the official Leeds United and Chelsea retro collections at 3Retro.com